Ouija Boards are a divisive topic and a staple of many slumber parties. While there are some who affirm that they bring nothing but trouble and should only be used by experienced occultists, others think they are little more than an amusement. In this blog post, we will explore the origins of the Ouija Board and how it came to have these two paradoxical reputations.

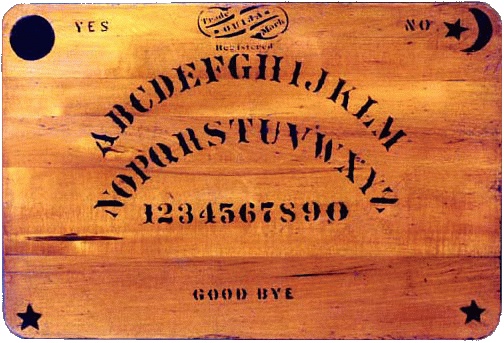

Unlike tarot cards which have a rather obscure origin story (which is discussed in this previous blog), the origins of the Ouija Board are well documented. The Ouija Board was first commercialised in 1890 in Baltimore by Kennard’s Novelty Company who advertised it as ‘a novelty fortune telling device’ similar to how we view a magic 8 ball today (Rodriguez McRobbie 2013; Peterson 2009; Murch 2016). This was at a time when interest in spiritualism was at its height in England and the USA, and seances were a popular pastime. Unfortunately, the lack of communication devices meant that mediums were forced to call out every letter of the alphabet and wait for the spirit to knock when they called out the correct letter (Rodriguez McRobbie 2013). Obviously, this was a rather drawn-out and cumbersome way to communicate with the dead. Enter the Ouija Board.

In 1886, US newspapers began reporting use of a ‘talking board’ in Ohio which was used to communicate with the spirits (Rodriguez McRobbie 2013). This was most likely a DIY invention by a medium who was looking for a more efficient way to contact the dead. Charles Kennard likely saw this advertisement and, along with three investors, established Kennard’s Novelty Company to make and market the talking board. Unsure what to call this device, the investors asked it, and it is said to have spelled out ‘ouija’. When they asked it what this means, the board is said to have replied ‘good luck’ (Rodriguez McRobbie 2013; Peterson 2009). The name and invention was then patented by Elijah Bond (one of the investors) who now has a Ouija Board gravestone (Walker 2014). A year later in 1892 when William Flud took over the company, he claimed that the name was a mix of the French word oui and German word ja which both mean ‘yes’ (Peterson 2009).

For most of its history, the Ouija Board did not have a bad reputation. It was originally sold as a novelty device and likely offered comfort to friends and family members of the deceased. This changed in 1973 when the movie The Exorcist was released (Rodriguez McRobbie 2013). The movie centres around a young girl named Regan who plays with a Ouija Board and then becomes possessed by demons. This is arguably when public opinion of the Ouija Board began to turn.

Today, there is no shortage of movies or personal anecdotes which claim that the use of a Ouija Board leads to bad luck, possession or death. Arguably, some of these claims may be purely made up for attention or revenue as is certainly the case for mainstream movies such as The Exorcist or Ouija: Origin of Evil. The same argument can be made regarding online posts which are designed to draw likes or shares. However, academic studies have also documented claims of paranormal behaviour in which the participants remain anonymous and so do not gain any fame or fortune for sharing their stories. A 1973 article from the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography documents a case of a cigarette flying out of a participant’s hand when the group asked the Ouija Board to prove its authenticity, and a later survey of 373 Ouija Board users found that 66 per cent of participants claimed to have had a bad experience with the board. (Quarantelli & Wenger 1973; Palmer 1999). These participants have nothing to gain by making these claims up.

However, just because a person believes that they are experiencing a paranormal event does not make it so. Chris French, Professor of Psychology and head of the Anomalistic Research Unit at the University of London, argues that seemingly paranormal movements may be nothing more than the ideomotor effect (2013). The ideomotor effect is an unconscious movement that we make when we are expecting a certain outcome or when we witness someone doing something and we unconsciously perform a sympathetic movement (French 2013; Shin, Proctor & Capaldi 2010). It has been used to explain strange happenings at seances since at least 1852 and is often used to explain the movement of Ouija Board planchettes (Shin, Proctor & Capaldi 2010). Still, there are those who absolutely swear that something inexplicable happened when they used the Ouija Board and that it definitely wasn’t faked. Indeed, YouTube features some Ouija Board footage which cannot be immediately debunked. Furthermore, even the Ancient Greeks used something called a psychomanteum (an oracle of the dead) to speak with the deceased and they certainly weren’t doing this for the YouTube views (Moody 1992).

What do you think? Are Ouija Boards just a bit of fun or something serious? Feel free to share your thoughts and stories in the comments below.

Photo credit

If you’re interested in purchasing the vintage 1950s William Flud Ouija Board, please visit Object Fix.

References

French, C 2013, ‘The unseen force that drives Ouija boards and fake bomb detectors’, The Guardian, 27 April, viewed 27 September 2017, The Guardian

Moody RA, 1992, ‘Family reunions: Visionary encounters with the departed in a modern-day psychomanteum’, Journal of near-death studies, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 83-121, Google Scholar, New Dualism, viewed 27 September 2017

Murch, R 2016, ouijas and weird-A’s, and witch-es, oh my!, Talking Board Historical Society, viewed 24 September 2017, http://www.robertmurch.com/ouijas-weird-witch-es-oh/

Palmer, J 1999, ‘A mail survey of Ouija Board users in North America’, The Journal of Parapsychology, vol. 613, no. 3, pp. 217, viewed 24 September 2017, Gale Cengage, Academic OneFile

Quarantelli, EL & Wenger, D 1973 ‘A voice from the thirteenth century: The characteristics and conditions for the emergence of a Ouija Board cult’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 379-399, ProQuest, Sage Publications, viewed 27 September 2017

Rodriguez McRobbie, L 2013, The strange and mysterious history of the Ouija Board, The Smithsonian, viewed 23 September 2017, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-strange-and-mysterious-history-of-the-ouija-board-5860627/

Shin, YK, Proctor, RW & Capaldi EJ 2010, ‘A review of contemporary ideomotor theory’, Psychological Bulletin, vol. 136, no. 6, pp. 943-974, EBSCOHost, viewed 28 September 2017, DOI: 10.1037/a0020541

Walker, A 2014, The guy who patented the Ouija board has a Ouija board gravestone, Gizmodo, viewed 24 September 2017, https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2014/11/the-guy-who-patented-the-ouija-board-has-an-oujia-board-gravestone/